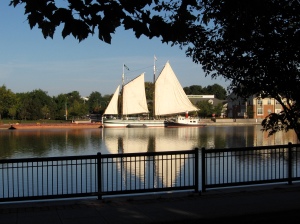

And show off in Rochester for the World Canals Conference we did. On September 18th, at 7:30 a.m., we set full sail (mainsail, foresail, and jib) to a light breeze from the south. Not that we got underway; we were tied securely to the wall. But for the next two hours, early

birds, including members of the press, captured the unique photographic image of a sailing canal boat with all her sails set in the Genesee River, a sight never seen before and one that will never be seen again. We lowered the sails and gave them a harbor furl before opening the boat to visitors at 10 o’clock. As 360 people came on board, we explained to each one that most canal boats seen in Rochester 150 years ago didn’t have masts and sails, that the few that did would probably have left them behind when they entered the Erie Canal, and that any that had kept their rigs on board (perhaps to sail on a Finger Lake) would have had them stowed on deck in Rochester because of the Erie Canal’s famous low bridges. (Folks sometimes ask, perhaps having somehow missed out on the song, if the Canal had bridges before the days of the trailer truck. Yes, indeed, and many more than today. One of the caveats when the Erie was first dug was that if the surveyors routed the canal across a farmer’s fields, the engineers and builders had to provide that farmer with a bridge.)

Over the next three days, we explained that our rig was up because of the World Canals Conference to many more citizens and also to school students who came on board. And some of the Lois McClure’s crew participated in the Conference. Museum Executive Director Art Cohn moderated a session on “Ports, Commercial Shipping, and Transport Infrastructure;” Museum Deputy Director Erick Tichonuk gave a thorough presentation on the Lois McClure, including her history, underwater archaeology, construction, the planning of her seven voyages, and her operation as a vessel for the teaching of history; and I demonstrated with pictures and words that the family-owned commercial barges carrying cargoes on the inland waterways of Europe are alive and well, still working much as did the canal boats on which the Lois McClure is based.

On September 22nd, we struck the rig and stowed it back on its T-braces, masts horizontal. For the next nine days we were to travel on the Erie through 31 locks on our way to Waterford, the eastern terminus of the Canal. The trip toward Waterford was uneventful until we got to Oneida Lake on September 27th. At some point during our calm, westbound crossing of Oneida on August 11th, I remember remarking to First Mate Erick Tichonuk, “I wonder what this lake will look like when we come back in late September?” Well, it looked quite different. No sooner had we towed the schooner out of the shelter of the Oswego River onto the lake than the wind that had been gentle breezed right up to fresh. Plenty of whitecaps. The C. L. Churchill, towing the schooner into the wind on the hip, began to dive into two-to-three-foot seas. Time to put her on the 200-foot hawser, towing the schooner astern. I should have turned 180 degrees and run off before the wind to make the switch. Usually, rigging the towline from the stern of the tug to the bow of the schooner and casting off the tug from the schooner’s side is the work of but a few minutes. This day it took longer. So while we were stopped to do it, the schooner’s bow had time to blow off, until the wind—and the waves—were abeam. The waves were just the wrong size for her narrow beam and flat bottom. My, but didn’t she roll! Would the big ballast stones stay chained in position? Would the masts, booms, and gaffs stay lashed in place overhead? Could the tug get out from under the lee of the schooner without damage? Well, thanks to fast action by the crew when the spars overhead did start to shift a bit, and thanks to a bold move by Erick, at the controls of the tug, no damage accrued. And thanks to every member of the crew taking care not to slip and fall on the wet, moving decks where they worked with lines to do what had to be done, no one was hurt. What a crew! Had we been running with the wind, the motion would have been far less.

Once the Churchill took a strain on the hawser and began towing the schooner into the wind again, things quieted down. The little tug is a gamer. She towed her much bigger charge against wind and wave at close to 4 knots. As we neared the shelter of the windward shore of the lake, the breeze went down, so putting the tug back on the hip to go into the canal was easy.

One of my objectives as Captain of the Lois McClure has been to give Erick, as first mate, every chance to gain shiphandling experience. In general, what we’ve agreed on has been I’ll do the potentially damaging stuff (like making a landing in a small berth between expensive fiberglass yachts) and Erick will do the less potentially damaging stuff (like landing on an empty wall where the biggest danger is “option paralysis:” where in that big space to put the schooner?). But recently, I‘ve realized I wasn’t challenging Erick enough. (That’s why he ended up in the tough position of getting the tug clear, with both vessels rolling together, when we put the tug out on the hawser on Oneida Lake.)

So, on September 28th, when we had to turn the schooner around in the narrow channel to land at Little Falls, Erick was at the conn. His landing was a joy to watch. He tucked the schooner’s bow in close to the wall out of the slow current and just let the movement of the water bring her stern majestically around as he shoved the vessel gently against the wall with the Oocher. Mercy.

By the next day, we were getting weather forecasts of prolonged, heavy rains. There was talk of flooding. We were on the Mohawk River, notorious for flood damage in 2006. We made plans for longer days’ runs, hoping to get off the river in two days, instead of three. So, on September 29th, we got underway from Little Falls soon after first light and made it all the way to Lock 10 at Amsterdam. We were going to go on further, to Lock 9, but when Art Cohn put the tug in gear to go “Slow Ahead” out of Lock 10, nothing happened. The engine’s torque was not being transmitted to the propeller!

I’ve always marveled at what a lucky ship is the Lois McClure. What went through my head at this moment was a conversation between God and the Crew:

God: (loud, deep voice from the sky) “You will break down today.”

Crew (soft voice from down here) “ Do we have to?”

God: “Because you have been good, you get to choose where.”

Crew: (slyly) “Could it be in a lock?”

God: “Oh, all right.”

How lucky can you get? Of all the places we might have lost power this day, inside a lock was the only safe one. What if it had been as we met the Governor Cleveland pushing a big barge? What if it had been when we were entering a lock with no way to stop? Well, we think about such emergencies and plan ways to cope, but still.

Lock 10’s keeper was already working late to get us through, and he stayed on to help us. He lowered the lock and we put the tug on the wall astern by hand, so that a yacht behind us could get by out of the lock and on her way. When he went to refill the lock, nothing happened! (Were we on Candid Camera?) He called in help to deal with an electrical problem. Eventually, up we went.

Art Cohn put on his snorkel mask and, leaning down over the Churchill’s low stern, put his head under to see what he could see. He saw that the propeller shaft had slipped aft against the rudder. A look at the shaft inside showed that the drive coupling had let go. This was not going to be a quick fix. Could we spend the night in the lock? Of course we could. The New York Canal Corporation takes such good care of us.

Erick, Art, Kerry Batdorf (our Ship’s Carpenter and chief fix-it man), and Andy Scott (an experienced licensed Captain who was volunteering) went to work. Four hours and a trip by Erick to the nearest Canal Corporation machine shop later (to convert a bag of broken metal parts from the drive coupling into new ones!), and the team was ready to effect a temporary repair that should put us back in business. Part of the job was to haul the aft end of the propeller shaft back up into position; this took both cranking on a come-along inside the boat and Art’s going underwater in his scuba gear, flashlight taped to his mask, to help it along with a hammer. It was nearly midnight before the crew had everything back together. The temporary fix meant that going ahead on the tug’s propeller should be no problem, because the forward pressure would hold things in place, but that going astern might possibly break it all loose again and leave us without propulsion.

The forecast was now definitely for flooding on the Mohawk on October 1st. So, when we got underway on September 30th, we wanted to get all the way to Waterford, or at least through the guard gate that protects the flight of locks down into Waterford from river flooding. With our shaky drive coupling, we determined to make the trip without ever going astern on the tug. Of course there might be some emergency that would require backing down, but otherwise all we need worry about was getting the schooner stopped when entering the seven locks on the way to Waterford. Our technique was to enter the lock chamber not just at slow speed, as we usually do, but at dead slow. We coasted in with bare headway, the schooner’s long, flat, well-fendered side just clear of the lock wall. Once in the chamber, we used the Oocher to push the schooner right against the wall, using the friction of the vessel’s rubbing along to bring her to a stop. More power from the Oocher was like stepping on the brake pedal a little harder. It worked. After a nine-hour trip, we tied up gratefully at our destination. Perhaps the sharpest sense of relief was when we looked astern and saw that guard gate being lowered into place.

That night the Mohawk River came up until the water was lapping at the doorstep of the Waterford harbor Visitor Center, about six feet above normal. The current in the river was running at five knots. It was good to be moored safely out of it.

By the end of the day on October 3rd, we had a new, improved drive coupling in place, thanks to professional help supplied by the Van Schaick Marina.

Next day, in Waterford, we had some 200 pupils from the nearby town of Salem on board. With grass instead of pavement, as on September 9th, Erick made his Lake Champlain-Hudson River-Erie Canal map with students instead of chalk. The half-dozen boys and girls assigned to emulate the river began bobbing like channel buoys! I guess he had their attention all right.

On October 5th, we left the Erie Canal and headed north on the canalized Hudson River. There was still extra current coming down, so our passage up to Schuylerville was a slow one, rewarded by another 80 school children on the 6th. On the 7th,we continued up river against the current, leaving the Hudson behind at Fort Edward to enter the Champlain Canal proper at Lock 7. Now, our 5 knots through the water gave us 5 knots “over the ground,” instead of 3.5 to 4.0.

Erick made another beautiful landing at Whitehall that required a 180-degree turn. Next day, he chalked his trademark map on the broad sidewalk along the mooring wall to the delight of 50 more elementary school pupils.

When the last visitor went ashore at 6 p.m. that day, she brought our total for this year’s trip to 11,460. That means that since the Lois McClure started voyaging in 2004, she has welcomed on board about 150,000 people. She has traveled some 5,000 miles and passed through about 300 canal locks.

I am finishing this log as the schooner lies quietly at anchor, tug on hip, off Fort Ticonderoga, on the New York side of Lake Champlain. We just had a beautiful run down the Lake from Whitehall. It has been one of those clear, northwest days, with every hillside, brilliant with autumn reds and yellows among the green, dazzling our eyes. And the weather forecast promises more of the same for tomorrow, when we will continue down the Lake toward home base, the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum at Basin Harbor, Vermont.

I am finishing this log as the schooner lies quietly at anchor, tug on hip, off Fort Ticonderoga, on the New York side of Lake Champlain. We just had a beautiful run down the Lake from Whitehall. It has been one of those clear, northwest days, with every hillside, brilliant with autumn reds and yellows among the green, dazzling our eyes. And the weather forecast promises more of the same for tomorrow, when we will continue down the Lake toward home base, the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum at Basin Harbor, Vermont.

Whenever I look back on one of these voyages that we are so privileged to make in the canal-boat-that-brings-smiles, I feel a great sense of gratitude to the crew, fine shipmates who take care of each other, of our many visitors, and of the vessels put in our charge. And I say another of many thank you’s to Art Cohn, the inspiration and guiding genius of the creation of the Lois McClure, not to mention the competent Captain of the tug, C. L. Churchill. These people and these boats have become a permanent part of me.

Roger Taylor

Captain