“Not a Particle of Liquor:” 19th Century Temperance

Overconsumption of alcohol in the early 1800s brought real, negative health and societal issues, many of which gave rise to temperance sentiments by the mid-19th century in Vermont and New York’s rural Adirondacks region. Temperance activists were inspired by Maine’s passage of a prohibition law in 1851, the first statewide law to prohibit the manufacture and sale of liquor in the country. In 1853, Vermont became the second state to enact a statewide prohibition law.

Above: Vermont took its cues from the Maine Liquor Law, pictured here in this 1852 political cartoon. Image: “Social Qualities of Our Candidate,” published by John Childs, New York, 1852. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Explore stories in this section:

From Local Option, to State Prohibition, to Local Option Again

From 1847 to 1852, Vermont voters (only white males at that time) cast their ballots annually to determine whether or not liquor would be sold in each county. Multiple towns flip flopped each year as to whether they would restrict liquor sales. After five years of this local control, the Vermont legislature passed, and Governor Erastus Fairbanks signed, a statewide law “to prevent the traffic in intoxicating liquor.” The law went into effect in March 1853, eliminating local control and centralizing this authority at the state level.

The law was referred to as the “Liquor Law,” and focused more on prohibiting distilled spirits than outlawing all alcohol. Production and consumption for personal, medicinal, or religious use were still permitted, but the law mandated that no person shall “sell or furnish cider or any fermented liquor to an habitual drunkard under any circumstances.” Those who did had to pay a $10 fine.

Statewide reaction to the law at the time was mixed. Religious and temperance groups rejoiced that the law was in place, while opponents of the law feared the negative economic implications and opposed the enforcement of such a wide-reaching state law.

Over the next 50 years, enforcement of the law was inconsistent and often impacted by corruption, racism, and classism. By the end of the 19th century, public opinion had returned to favoring more local control over liquor laws, and, after another statewide referendum, Vermont moved back to the “local option” in 1903.

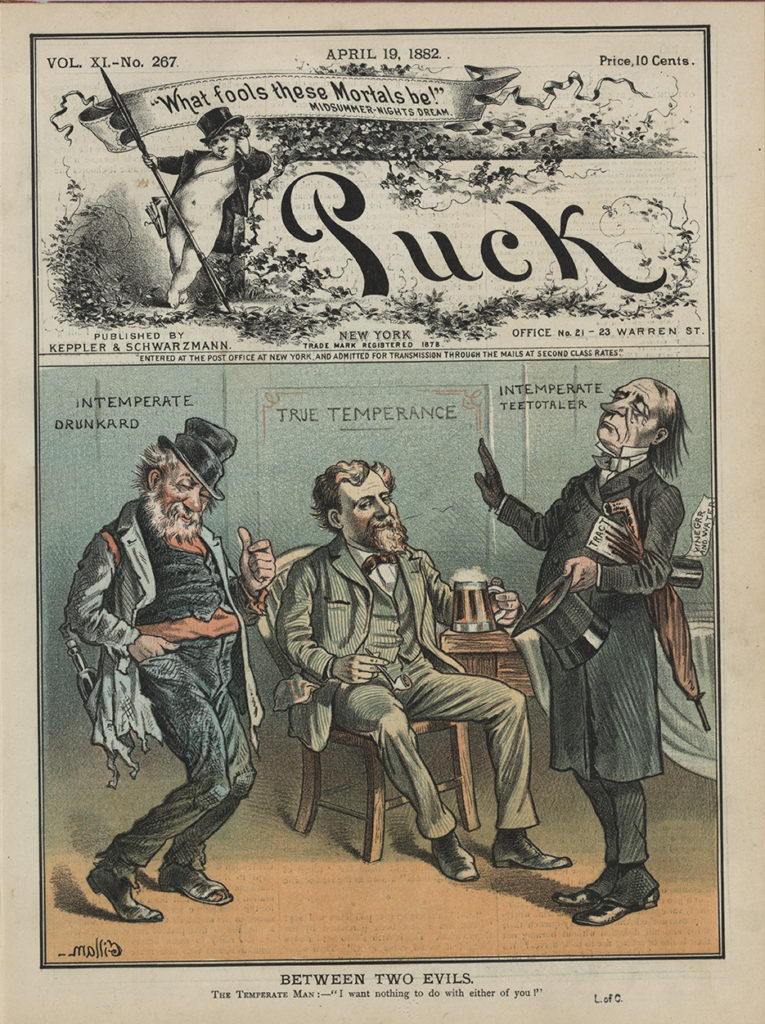

Image: Between Two Evils, Illustration from Puck, v. 11, no. 267 (April 19, 1882), cover. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Temperance in the Adirondacks

New York never passed statewide prohibition in the 19th century, mainly due to anti-temperance sentiment in the major urban areas. However, there was widespread support for temperance in the New York counties bordering Lake Champlain. The rural spaces themselves came to represent purity, cleanliness, and temperance in the 1800s.

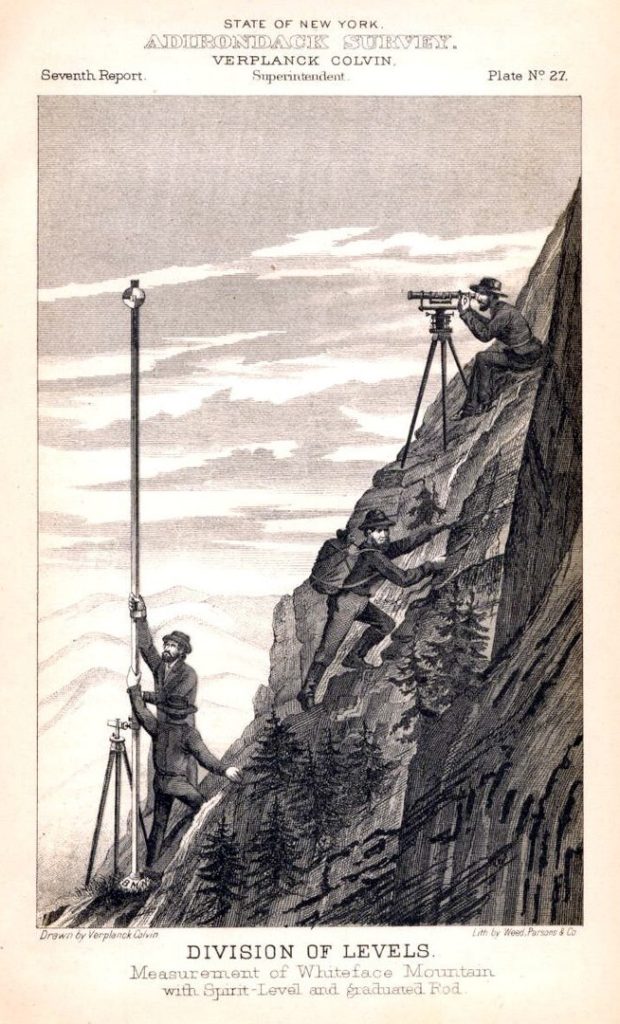

Verplank Colvin, who surveyed the Adirondacks in the 1870s, credited his success partly to temperance policies on his expeditions. The pure waters of the mountains were all his men needed for moral and scientific success. “Not a particle of alcoholic or fermented liquor of any kind…was used, carried or permitted to be used…the result has been subordination, steady work, health and success.”

Image: “Division of Levels — Measurement of Whiteface Mountain with Spirit-Level and graduated Rod”, drawn by Verplank Colvin, published in the Seventh Report of the Adirondack Survey, 1879. Published Albany State Printer: James B. Lyon, 1881.

How to Enforce a Complex Law

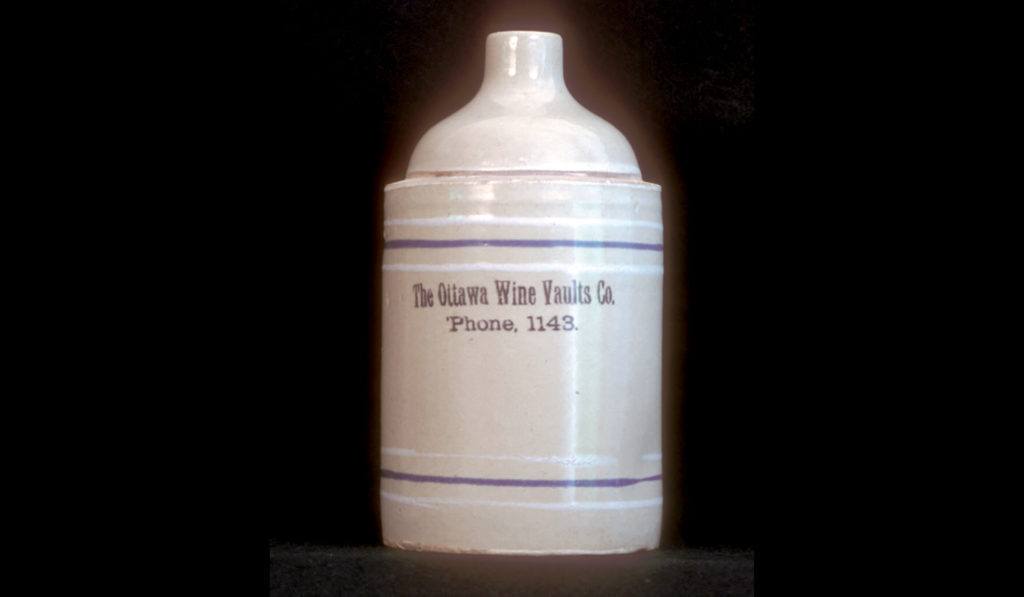

The Jug Case became known across the country for testing the limits of inter-state commerce laws when it came to preventing the sale of alcohol. In the 1880s, during Vermont’s statewide prohibition law, a merchant in Whitehall, NY, named John O’Neill ran a mail order alcohol business. Vermonters would put their jugs on the train in Rutland, the train would bring empty jugs to Whitehall, he would fill the jugs in Whitehall, and put them back on the train. After that, Vermonters would pick up their jugs from the train station. Vermont issued a warrant for O’Neill’s arrest, but New York would not enforce the warrant. O’Neill turned himself in to Vermont authorities, where he spent time in jail and paid a large fine. His case, which became known as the Jug Case, went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court ruled that because the sale of liquor was completed in Vermont it was not a federal issue but instead was subject to the laws of the state of Vermont.

Plenty of Vermonters ignored the Liquor Law, and Catherine Dillon was one of the most well-known repeat offenders. Dillon owned a boarding house and hotel in St. Albans and was repeatedly arrested, jailed, and fined, but was never severely punished enough to deter her or hinder her resources. In 1871, the Burlington Free Press wrote, “Catherine had well-developed relationships with those responsible for enforcing the laws and benefited from their assistance.” Her story is emblematic of the corruption and uneven enforcement of this statewide prohibitory law, which often didn’t prohibit much of anything.

Image: This jug was excavated from the Sloop Island Canalboat shipwreck site in Lake Champlain and is most likely from the early 20th century. Ottawa Wine Vaults jug, Sloop Island Canalboat, Lake Champlain Maritime Museum Collection.