by Art Cohn

When last I wrote, the Lois McClure and her crew were about to proceed down the Rideau Canal from Ottawa to Kingston. Traveling this historic waterway southward reveals a canal very much like it was in 1832. The stone locks have never been expanded and the five-foot depth-of-canal is unchanged. The same narrow twists and turns that challenged the mariners of yesterday navigating steamboats towing barges or timber rafts are still the course. That said, the further we traveled on this canal the more enchanting it became. In Merrickville, the community hosted us for a grand evening reception at one of the large blockhouses built in contemplation of continued war with the United States. It felt a bit strange to reflect on the origins of the fortification so rooted in conflict but now “hosting the enemy” is a clear acknowledgement of our strong national ties. Our next stop at Smith Falls revealed a city in the wilderness and spoke of the canal’s commercial impact to this once frontier community. However, when we left Smith Falls for Kingston, the canal became even more like turning a page back in time.

The twists and turns of the canal were part of the charm and part of the challenge. It spoke of the British Royal Engineers’ focused military goals to connect the Ottawa River to Kingston on Lake Ontario for the next war. The canal did not have to be straight, it just had to allow troops and supplies to bypass the vulnerable St. Lawrence route. Each lock we passed had its own unique history, but the locks at Jones Falls proved to be in a class by themselves. Everyone we spoke to along the way had said that Jones Falls would be the high point of the canal and that the remarkable series of locks, turning basin, and stone dam was a triumph of engineering. The site was even more remarkable because of the 1877 Kenny Hotel, a still operating connection to the 19th century “back to nature” fishing and boating era. But what really made Jones Falls a true time capsule was the written record left by Peter Sweeny, the first Jones Falls lockmaster, His “Diary” written from 1839-1850* was a present to me from my fellow crew member Jean Belisle. The journals provided a picture of life along the new frontier waterway as well as a glimpse of steamers, barges and rafts that typically began navigating the system in late April and continued until late November or early December.

*The Sweeney Diary: The 1839-1850nJournal of Rideau Lockmaster Peter Sweeney. Edited by Ken Watson. Friends of the Rideau. Smith Falls, Ontario, 2008.

Our crew had heard so many positive descriptions about Jones Falls that we were able to make some modest adjustments of our travel schedule so that we could spend an afternoon and evening there while en-route to Kingston. Jones Falls, like the rest of the canal, is operated by Parcs Canada and in addition to the well maintain canal infrastructure, this site includes a working blacksmith shop and an interpreted “fortified” lockmasters house where Peter Sweeny penned his journal. The flight of locks separated by the turning basin was so beautiful you could have convinced me that the designers laid it out to maximize its presentation and not for utilitarian purposes.

The 60-foot high stone dam was, at the time, a marvel of engineering and still serves today to create the canals required water levels. After a short but remarkable stay at this oasis in the woods, the next morning the crew prepared to embark for our final leg to Kingston. Saluted by the other boaters at the bottom of the flight, our sendoff included a talented bagpiper playing us off to Kingston, the fortified town that had served as British naval headquarters on Lake Ontario during the War of 1812. Arriving at Kingston on the canal and Lake Ontario was like emerging from the wilderness into the city.

Descending down the final flight of locks at Kinston Mills for a short transit on the Cataraqui River we arrived at Kingston Marina which is also the home of Metalcraft Marine, makers of high speed patrol, fire-rescue and work boats. We had arranged to put up our sailing rig here for our stops at Kingston, Sackets Harbor and Oswego. Rigging Lois is a time-consuming difficult job but when it was completed we received another unexpected gesture of community support. The rig was installed utilizing the marinas big stationary crane operated by Sandy Crothers, the marina manager. It was a multi-hour and complicated job, but when it was finished Sandy informed us that after talking with the other marina and Metalcraft principals, they had decided that they appreciated our outreach mission enough that they had decided to waive all our fees. The crew was all deeply touched by this unexpected gesture of generous support.

Kingston, Sackets Harbor and Oswego are all important locations in our War of 1812 commemoration story. Kingston had been the British naval base on Lake Ontario which competed with its American counterpart at Sackets Harbor in what has been called “The Battle of the Ship Carpenters.” In these two naval shipyards, the race to advantage in size produced ship-of-the-line warships capable of carrying over 100-cannon. The Naval Commodore’s on both sides of Lake Ontario produced impressive squadrons that only sparred but never came into decisive action. At war’s end, some warships were sold, some were broken up and others sank destined to become subjects of our modern nautical studies. Both Kingston and Sackets Harbor still contain the tangible legacy of this impressive shipbuilding effort and in 2013 shipwrecks from the war will be featured in a new book edited by Kevin Crisman entitled Coffins of the Brave: The Nautical Archaeology of the Naval War of 1812 on the Lakes.

After our rigging was installed, we moved to our public venue on the Kingston Waterfront next to the Holiday Inn. Our community partner was the Maritime Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston who had also invited me to do an evening lecture on shipwreck management. The lecture was well attended and I talked about the 1776 gunboat Spitfire and the 1812 Confiance Anchor Project, as two examples of current management case studies. Our public days at Kingston Harbor were busy and satisfying as many people showed up to learn more about the War of 1812 and the Rideau Canal system built in its aftermath.

When our time in Kingston was concluded we prepared for crossing of Lake Ontario and while the crew hoped this might provide an opportunity to unfurl the sails and show our schooner at its best, we were cautious. We have a reference from Captain Bartley’s crossing from Oswego to Kingston being towed by the tugboat Charly Ferris back in 1886. He described the wind being moderate on the day he crossed, and “there appeared to be no sea,[but] there was a long heavy swell from the west [and] the boat rolled to her scuppers…” The conditions for our crossing did not line up the way they needed to and we had to be content towing ahead with our beloved C.L. Churchill and crossing the big lake with our schooner under tow. Our passage to Sackets Harbor was uneventful with calm wind and seas, but when we set out from Sackets Harbor to Oswego we recreated Captain Bartley’s experience in that although we had little wind to speak of, the swell was very impressive and at times the Churchill “rolled to her scuppers”.

Sackets Harbor was one of our important War of 1812 commemorative stops. In addition to the naval activity there, it became an impressive complex of fortifications built to protect the naval shipyards. After the war, the stone Madison Barracks were built to strengthen the US position for the next war. Happily, the next war never came and the huge warship New Orleans being built on Navy Point was never finished and instead became a curiosity for travelers. Today Navy Point is a private marina and the Madison Barracks have been adapted to private housing. The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation (OPRHP) operate the historic site of the military fortifications.

I found that upon entering the historic harbor I experienced a warm and familiar feeling about returning to Sackets Harbor. In the mid-1980’s, fresh from completing our study of the US brig Eagle in Lake Champlain, Kevin Crisman and I had gone to Sackets to see if we could locate the remains of the US Brig Jeffersonwhich was reported to be sunk within the harbor. We were successful and that discovery led to a multi- year study were we had the help of Sackets Harbor historians Bob and Jeannie Brennan. Bob and Jeannie had been our community liaison and hosts but I had not been back to Sackets harbor in more than 20-years and wondered if Bob might still be there. We had not been in town very long when Bob and Jeannie made contact and we arranged to meet down at the boat. It was so good to see them both and we exchanged many recollections of our time there. Bob had made it possible for us to find much needed housing for the crew and had provided us with much historical information.

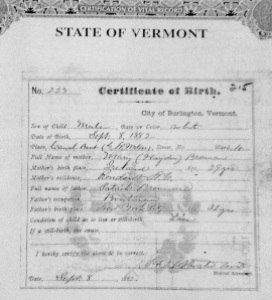

While we were reminiscing, Jeannie reminded me that Bob’s father had actually been born on a canal boat based out of Kingston, NY. She recalled that in those days if a baby were born on the boat it was typical to register the baby in the next community the boat landed. In this case of small world stories, the Brennan’s next stop had been Burlington and Jeannie made me copies of Bob’s father’s birth certificate which told us his “Place” of birth was the “Canal boat G.N. Waters.” To make the small world smaller, our contact at Sackets Harbor was NY OPRHP Site manager Constance Barone, who is Bob and Jeannie’s daughter.

We arrived on a beautiful day and tied up at the town dock and park and almost immediately began talking to people. We had the time to explore the historic sites, Visitors Centers and museums that make Sackets Harbor such an interesting place. One big change from our dive project days is that downtown Sackets Harbor is now the venue of an impressive collection of restaurants and one GREAT ice cream shop that Jean and I frequented almost every night. The Ontario Place Hotel were great hosts and provided the crew with a place to shower…no small kindness to a traveling crew. By the time we opened on the weekend, the word of our presence had spread in many conversations and translated into an extraordinary weekend with a turn-out of over 1700 visitors!

At Sackets Harbor I was very pleased to be asked to do a program about the shipwreck in Sackets Harbor and other stories on Saturday morning. It was set for the gazebo in the town park right next to the dock and an enthusiastic crowd attended. I was able to simply look across the harbor to the orange buoy and explain to the group that it marked the resting place of the 20-gun American brig Jefferson. The Jefferson had been built by master shipwright Henry Eckford one of the nations most talented builders. It had been Eckford who had performed miracles in building many of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s fleet that achieved victory at the 1813 Battle of Lake Erie. As I toured the OPRHP Sackets Harbor Battlefield site I was very pleased to learn that information from Kevin and my studies were incorporated in the exhibit at the Battlefield entitled “Life Aboard the Jefferson”. I also was very gratified to preview a new exhibit that is scheduled to formally open next May about the Archaeology of Sackets Harbor, which features our work on the Jefferson. All in all, Sackets Harbor had to be one of the most wonderful and rewarding stops in a tour. I hope we can go back!

Special Thanks to:

- Parcs Canada

- Heritage Canada

- Maritime Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston

- Constance Barone

- Sackets Harbor Visitor Center

Art Cohn

Captain, C.L. Churchill

Thanks for sharing such a fastidious opinion, post

is fastidious, thats why i have read it completely