By Paul Willard Gates, Co-Director of Archaeology

As many people, communities, and cultures celebrate Halloween today with costumes, trick or treating, remembering the dead, telling scary stories, or visiting supposedly haunted attractions, our Archaeology and Research team recommend you take a moment on Halloween to look below the waters of Lake Champlain. Did you know that Lake Champlain is home to several ship graveyards? What could be spookier than that?

The maritime heritage of the Lake Champlain Valley region is a rich and fascinating history stretching across thousands of years and vessels plying the waters of the lake. While we have a good understanding of many of these boats and the people who used them, there are numerous ships and wreck sites below the lake whose stories remain relatively unknown. As the underwater cultural resource managers of Lake Champlain, the Archaeology and Research team at the Museum studies and researches the underwater archaeological sites of these unknown vessels… better known as ship graveyards. Oooooooo!!!! Ahhhhhhh!!!! How frightening!!!

While shipwrecks have been of interest to underwater archaeologists world-wide since Underwater Archaeology was recognized as a formal discipline of science in the 1960s, studies on ship graveyards have only been of note in the past fifty years (NOAA 2024; Richards 2008:17), particularly as they relate to research of ship abandonment and human decision making in the discard of vessels. The term “ship graveyard” is understood as “accumulations of watercraft retired and abandoned by their owners following a decision that their vessels are ineffective or inadequate for their intended purpose (Richards 2008:27).” These cemeteries of amassed wrecks represent a dumping ground for ships that were no longer able to work, metaphorically associated with scrapyards where people get rid of their old, dilapidated automobiles.

The ship graveyards in Lake Champlain that archaeologists from the Museum and other academic institutions have studied include several notable areas such as the Pine Street Barge Canal, the Shelburne Steamboat Graveyard, and the South Bay Canal Boat Graveyard Historic District. Take a quick tour of these sites with us:

The Pine Street Barge Canal Ship Graveyard and the Breakwater Basin Ship Graveyard in Burlington, VT contains ten vessels spanning from the middle of the nineteenth century to the latter half of the twentieth century. The canal became a dumping ground since 1895 for waste by-products from a coal gasification plant located nearby, which included coal tar, fuel oil, cinders, and cyanide (Kane et al. 2007). The location of the vessels in the Pine Street Barge Canal Ship Graveyard, a designated United States Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site since 1983, represent the remains of 1873 class canal boats that were abandoned in the 1920s or 1930s (Kane et al. 2007). This period coincides with the very end of the canal boat era and was chosen as an ideal location for the deposition of these well-used vessels once they reached the end of their use-lives.

Research on the vessels in the Pine Street Barge Canal Breakwater Basin Ship Graveyard uncovered the remains of the lake schooner Excelsior, the converted stone ferry tugboat Hildegarde, and three construction barges used to rehabilitate the Burlington Breakwater in the 1960s. The abandonment of the first vessel Excelsior in 1884, after a lengthy career as a bulk cargo carrier made in 1850 at Willsboro, NY, is indicative of its demise in the face of changing technological trends in transportation, making a cargo ship obsolete. Hildegarde was originally a racing yacht made in 1876 in Islip, NY. The vessel was eventually converted through a series of iterations as a freighter, car ferry, and then a stone ferry tugboat until its untimely end in 1937 due to age and deterioration. The construction barges made in 1960 for the Turner and Breivogel construction company located in Falmouth, MA were used to ferry stone to the Burlington Breakwater for rehabilitation. Though in the years of hard use, wear, and tear they were abandoned in 1964. All of these vessels share a common theme in being discarded due to age, deterioration, changing technological trends (Gates 2019).

Next on our ship graveyard tour, the Shelburne Steamboat Graveyard in Shelburne, VT is a particularly interesting site that has the remains of four steamboat hulls. The remains of the vessels are early nineteenth century passenger steamboats owned by the Champlain Transportation Company. The four wrecks are believed to be the steamers A. Williams (1870), Phoenix II (1820), Burlington (1837), and Whitehall (1838) (Institute of Nautical Archaeology 2024). One of the most fascinating aspects of this steamboat graveyard is that all the vessels are examples of early steamboat construction techniques. After the end of Robert Fulton’s monopoly on steamboat patents, builders in the Lake Champlain region started to devise ways of making larger, faster, and stronger steamboats that could successfully navigate the lake. Thanks to extensive research done by Dr. Carolyn Kennedy of Texas A&M University’s Nautical Archaeology Program, we have a better understanding of the technology and techniques used in early nineteenth century steamboat construction (Kennedy 2015). Like any old boat, they reached the end of their use-lives and were abandoned to the graveyard.

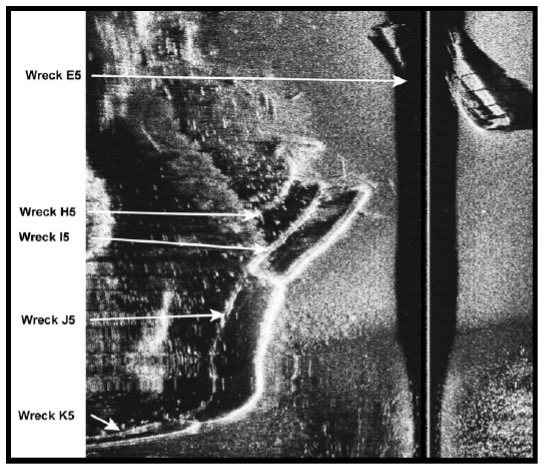

Last, but not least, the South Bay Canal Boat Graveyard Historic District just west of Whitehall, NY represents a collection of at least seven canal boats abandoned in the early twentieth century (Kane et al 2007). Since the 1980s, researchers and archaeologists have been aware of this collection of canal boats. However, the mystery of their historical context persists. What is known is that their dimensions are indicative of 1873 class canal boat – the very last canal boat type made regionally before the older canal systems such as the Champlain Canal fell out of use after construction of the larger Barge Canal system in New York state. Other evidence suggests the time period of the early twentieth century in which they were abandoned, supported by their location near the remains of a bridge from 1917 that was replaced in 1930. Interestingly, none of these vessels are located near the remains of the 1930 bridge. The period of abandonment from 1913 to 1930 is consistent with the end of the canal boat era along with the subsequent abandonment of other similar vessels in Lake Champlain. As these vessels became obsolete in the face of larger canal boats, they were left to lie deep in their watery graves.

Ship graveyards are interesting and historically significant collections of vessels. As the last resting place for abandoned vessels in Lake Champlain, all three of the graveyards discussed represent the end of specific eras of maritime history. While there are only the proverbial bones left of these ships, they all contribute to tell us more about the archaeology of watercraft abandonment practices in the region. As Halloween is here, the underwater archaeologists at Lake Champlain Maritime Museum want to wish you a festive, safe, and spooky time. Our underwater ship graveyards will be here for you to learn from and appreciate for their cultural heritage! Maybe haunt your dreams too!

References

The Burlington Free Press, 1962. How To Build a Breakwater. The Burlington Free Press 30 August, (208):17. Burlington, VT.

Institute of Nautical Archaeology, 2024. Shelburne Shipyard Steamboat Graveyard Research Project. https://nauticalarch.org/projects/shelburne-shipyard-steamboat-graveyard-research-project/, accessed 20 October 2024.

Gates, Paul Willard, 2019. What Lies Beneath at the Pine Street Barge Canal Breakwater Graveyard: Site Formation Processes as a Document of Change in Burlington, Vermont (C. 1930-1960) Master’s thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Kane, Adam I., A. Peter Barranco Jr., Joanna M. DellaSalla, Sarah E. Lyman, Christopher R. Sabick, and Arthur B. Cohn, 2007. Lake Champlain Underwater Cultural Resources Survey, Volume VIII: 2003 and Volume IX: 2004 Results. Report from the. Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, Vergennes, VT.

Kane, Adam I., Joanne M. Dennis, Scott A. McLaughlin, Christopher R. Sabick, Arthur B. Cohn, 2010. Sloop Island Canal Boat Study: Phase III Archaeological Investigation in Connection with the Environmental Remediation of the Pine Street Canal Superfund Site. Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, Vergennes, VT.

Kennedy, Carolyn, 2015. Shelburne Shipyard Steamboat Graveyard: Archaeological Investigation of Four Steamboat Wrecks. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station TX.

National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2024. Underwater Archaeology <https://marineprotectedareas.noaa.gov/toolkit/underwater-archaeology.html>. Accessed 17 October 2024.

Richards, Nathan, 2008. Ships’ Graveyards; Abandoned Watercraft and the Archaeological Site Formation Process. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL.